Open

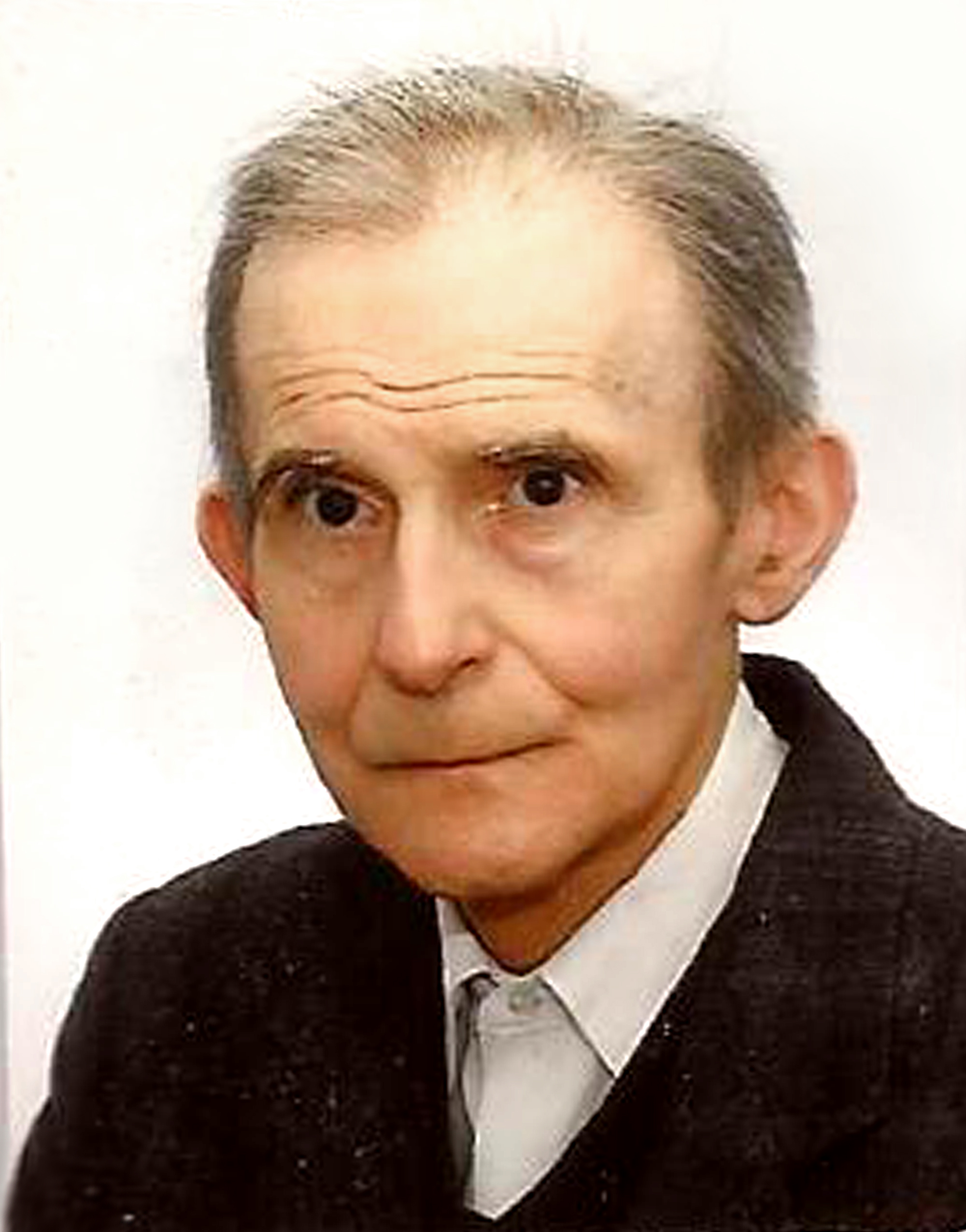

Dr. Andrej Kreutz Dr. Andrej Kreutz

EGF adviser on trans-Atlantic security

When discussing the place in the international system and the foreign policy of any major country, one needs to take into account its historical background and the transformations of its image in the eyes of the world. Because of the special and rather unusual features of both Russia’s geopolitics and history, the need to do that seems even more necessary.

Russia’s relations with the West, which since the end of the 13th century became its main political partner and antagonist, have seldom been simple and easy, and Western European perceptions of the country, which in the early modern period was called Muscovy, were predominantly negative. It did not necessarily mean that Western Europeans or Poles living at that time had a good or amicable attitude towards their other neighbours, and even less to the peoples of Asia and newly discovered continents. However, it seems to me that their image of Russia and its inhabitants was still more critical and even more hostile than towards other peoples.

A respected German scholar and diplomat, Adam Olearius, who had visited Russia several times between 1634-1643, and whose work published in 1647 had influenced European opinion on this country in the 17th century, wrote on Russians that: “If a man considers the nature and manner of [their] life he will be forced to avow there cannot be anything more barbarous than that people.”(1)

About a century earlier, an Elizabethan poet and the secretary of the English Embassy in Moscow (1568-69) George Tuberville was apparently more benevolent and just compared Russians with England’s most hated and despised neighbours, the Irish. According to him “Wild Irish are as civil as Ruses in their kind; hard choices, which is best of both, both bloody, rude and blind.”(2)

The title of the accounts of English travellers to Russia in the 16th century, Rude and Barbarous Kingdom. Russia in the Accounts of the Seventeenth Century English Voyages(3), speaks for itself, and a no less alarming picture of the country was presented by various German publicists and Polish diplomats who, at that time, had to directly face the growing power of Moscow.

The opening of Russia to the West which has increased since the 17th century and even some successful interventions in European politics did not much to change its reputation and did not dissipate the persisting prejudices. The victory in the Northern War with Sweden and the Nystad treaty in 1721 marked the final recognition of Russia as a European power (4) which was going to play a leading role in the continent during the first decades of the 19th century, including the Napoleonic Wars and the Vienna Congress in 1815. However, the most influential description of the country in this century by the Marquis de Custine’s, La Russie en 1839 (Paris, 1843), was entirely hostile and negative. This attitude was predominant in the West until the Russian Revolution in 1917. Relations with Saint Petersburg were seen as a political necessity, often running against domestic public opinion. “The Bolshevik revolution in October 1917 and the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1922 made Moscow’s relations with the West even more complex and difficult. The Cold War period between 1946 and1986 aggravated the existing situation and caused Russia to be seen as the world enemy of the Western community. However, the collapse of the Communist system and the end of the Soviet Union in December 1991 did not bring an end to the pre-existing mistrust and disappearance of the perennial “Russian Question.” What were its causes and what are the prospects for its more benign solution?”

Russia’s relations with the West were full of political conflicts and social and cultural misunderstandings, which were apparently difficult to avoid. In addition, there were probably four major reasons for such long-lasting alienation.

- 1) The first, and from an historical point of view the oldest, was isolation from Europe and Western development of the Russian lands lasting more than three centuries. The German historian Eduard Winter argued that Muscovy had left Europe when it fell under the Mongol Tatar yoke in the first part of the 13th century, but “once again became a full partner in the European association of nations” in the second part of the 15th century. At that time, it had regained its independence and the Grand Duke Ivan III’s marriage to the niece of the last Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI , Zoe Paleologue, signified Moscow’s acceptance as a European power . However, Professor Winter was too optimistic in his judgement. Russia’s route to Europe and the Western community was going to be much longer and probably still has not been completed. There were at least four other obstacles to that.

- Religion. Russia was Christian but an Eastern Orthodox nation, and in contrast to Germany and Poland, it received its religion not from Rome but from Byzantium. Relations between the two major branches of Christianity, Eastern and Western, sharply deteriorated from the 11th century and even more so after the conquest of Byzantium by Crusaders in 1204. The political and cultural implications of that were long-lasting and also had a major impact on the development of their nations and their mutual relations.

- The third and probably the most important reason were Russia’s geopolitics and what was related to it, the political and socio-economic situation in the country. It had always been a huge country with, relative to its size, a sparse population and a very harsh climate. Being located on the East-European lowlands, it was exposed to numerous invasions from the East and the West, and yet, in spite of all these adversities, Russia was the only non-Western and in some way non-European empire “to remain a powerful independent world historical state throughout the modern period”(5). According to an American historian, “Russia accomplished this remarkable fact… because of a highly effective, durable and resourceful political system-autocracy” (6) which allowed the Russian ruling class to pursue an alternative path to early modernity (7). Though the American scholar seems to exaggerate the point, the fact remains that the Russian way of development differed from the Western one. That made its relations with the Western powers so complex and often difficult. As Winston Churchill said, for many Western leaders Russia seemed to be “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma”.

- The country had not thus been a part of the West as it was established in the medieval and early modern period, and expanded after that to some other parts of Europe, such as Poland, and to the newly discovered parts of the world. At the same time it was still a Christian country and, in spite of its backwardness compared with Western nations, it had a centralized and efficient political system which enabled it to mobilize a substantial military power if needed. For those two reasons, it was difficult to treat Russia in the same way as the Western explorers treated Indigenous populations in America, Africa, India or Australia. In addition, because of its geography and extreme climate, for the most part it was not practical to think about its conquest and direct subjugation in the same way as for many other non-Western peoples of the era.

As an outcome of that, Russia was for a long time left in a somewhat grey area and lacking a determined legal and political status. It was neither fully accepted as an equal partner nor rejected and submitted to a direct Western control and this situation contributed to dislike and fear of Russia in Europe. The French scholar and clergyman Chappe d’Autoroche, who travelled throughout Russia in 1760, wrote that “In France people expected her to overrun our little Europe, like the Scythians and Huns. Hamburg and Lubeck trembled at her name. Poland and Germany considered Russia as one of the most formidable powers in Europe.” (8) However, according to the French visitor, Western fears of Russia were unfounded (9) . Both the country itself and its army were socially too backward and devoid of proper training and equipment to be able to present any real threat to the more developed European powers. The case of Poland and its then forthcoming partition was a special one because, as L’Abbe Chappe noticed, “The sovereign [there] was without authority and the state without defence, and it was open to any invader” (10). Nevertheless, such a fear still persisted for centuries and contributed to the negative feelings toward the country.

On the Russian side, the situation of long-lasting social and material backwardness in relation to the Western nations was also causing fear and mistrust of the more developed powerful and by no means friendly countries. As a result Russian relations with the West have often been tense and unpredictable. However, in their long history there were also periods of mutual cooperation and common achievements which were very beneficial for the West, including the joint struggle during World War II against the Axis, Gorbachev’s time of “new thinking” and his foreign policy revolution, and even Putin’s support for the US war against terrorism after September 11, 2001.

Unfortunately, none of them have been long lasting and in the aftermath of all of them, Moscow did not achieve any tangible rewards or recognition. The Soviet victory over Nazi Germany in World War II opened the door to American domination of Europe, and, after Washington’s refusal regarding the neutralization of Germany, to the Cold war with all its consequences which were fatal for Moscow. Gorbachev’s international policy and opening up to Western demands contributed to the collapse of the Russian power and the impoverishment of its inhabitants, and all Putin’s concessions after 2001 were reciprocated by further NATO expansion in Russia’s neighbourhood, the IBM deployment there and the launching by the West of a global strategy of regime change in “rogue states”. The current situation in the Middle East and its possible world-wide implications cannot provide a reason for any optimism, and the long economic crisis and growing imbalance of military power can lead to some unpredictable and possibly tragic events.

Present-day Russia is trying to recover from its last “time of trouble” (smuta) of the Gorbachev-Yeltsin period and the end of the USSR. It was the second such critical period in the 20th century, together with the 1917 Revolution and the collapse of the Tsarist Empire, which is compared with the tragic events in early 17th century Russian history. However, according to Western experts, the presently existing chances of a successful recovery are much more limited than in the past. Even some Russian liberals such as Dmitri Trenin agree that the Russian phoenix cannot be reborn again and that the Russian moment in world history has come to an end. It is difficult to predict the future, but the existing and potential challenges for Russia seem in fact to be formidable.

As Thomas Graham indicates, the country’s geopolitical context has changed to Russia’s disadvantage. As he writes, “for the first time since it emerged as a great power, it is surrounded (beyond the former Soviet space) by the countries and regions that apparently seem to be more dynamic than it economically, demographically and politically.” (11) Although the situation there is probably not as clear-cut as he wants to suggest, and we can notice many contradictory events taking place, the fact remains that the decline of Europe which has definitely lost its centrality in global politics, does not seem to work to Russia’s advantage. The new and still ongoing industrial revolution and the socio-economic transformations of the society which were involved by it are still more difficult to absorb than the previous ones, and Russian access to the new technological developments are even more difficult because of the persisting American control over the most developed countries and the internal Russian social problems. Last but not least, the US superpower definitely does not want to recognize Moscow as an independent political and economic center, as it was done in the case of China, India, and even Saudi Arabia, and during the last years we are seeing an unprecedented American soft power campaign against both the Russian leaders and the country itself.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the nature of power itself has changed, or at least was submitted to substantial modifications. The information revolution skillfully manipulated by the American elites and American pop-culture, which as Zbigniev Brzezinski had admitted, they propagated, provided them with previously unknown tools of influence on the rest of the world, also including at least some parts of Russian society. The fact that after 2006 (12), but especially during and after the recent parliamentary and presidential elections in the country, Russia became an object of a massive and well organized mass media campaign all over the Western-dominated world, is certainly very detrimental for the country’s image and its future prospects. However, in my opinion the total submission to American and Western demands would not alleviate Russia’s major challenges, and it would probably put it in a much more difficult situation. Just as in the past, Russia needs its own way and methods for a new modernization which does not preclude, but rather implies its independence, originality and use of all its previous achievements. In addition, not only Western Europe, but also North America now seem in a complex economic and socio-political crisis, the future outcome of which is difficult to determine. At the time when the neo-liberal models and the Washington consensus are widely criticized in the Western countries including the United States itself, to implement them en bloc in Russia would probably be too rash or at least premature. The development of every nation predominantly depends on its environment, its past, and its specific situation, and although the autocratic system in either the Tsarist or Soviet forms is obviously outdated, and Russia needs to cooperate with the West and learn from it, nevertheless it should try to find its own way towards the future.

- Fransesca Wilson. Moscovy. Russia Through Foreign Eyes. 1553-1900 (New York. Praeger Publisher, 1970). P.71.

- ”A people passing rude, to vices vile inclined”. As reprinted in Anthony Cross, Russia Under Western Eyes 1517-1825 (London: Elek Books, 1971) p. 71.

- Philip Longworth, “Muscovy and the Antimorale Christianitatis”, Guyla Szvak ed., The Place of Russia in Europe (Materi Op al of International Conference, Budapest, 1999) p.83.

- Eduard Winter, Russland und Papstum, vol1, Berlin 1960, p. 179.

- Marshall T Poe, The Russian Moment in World History (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2003)p.47.

- Op. cit p. 70.

- Ibid.

- Francisco Wilson, op cit, p. 142.

- Ibid.

- Op. cit. p. 134.

- Thomas Graham “ Russia and the World” Russia 2020 (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Russia in 2020: Scenarios for the Future, ed by Maria Lipman and Nikolay Petrov, Chapter one.)

- Russia Wrong Direction: What the United States Can and Should Do (Council of Foreign Relations, March 2006).

0 Pros 0 Pros 0 Cons 0 Cons

|

|

Comments 0